The author, in her Halloween splendor.

I won Halloween last night.

Let’s back up:

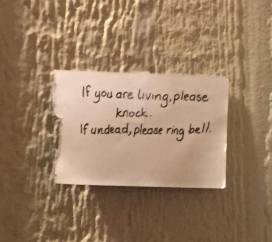

I used to hide from trick-or-treaters because of some weird introvert issues, so I’d just let the doorbell ring. Over the years, though, hiding from the doorbell on Halloween has become an even bigger anxiety fest for me. For the last several years I’ve been away at conventions on Halloween, avoiding the whole question about whether I’d give out candy at home. This year, I found myself home alone on Halloween night, so I had a long think about what exactly triggers my anxiety. Once I narrowed it down to the doorbell, I knew what I could do. I could make the doorbell inaccessible. So I covered it with a sign:

“If you are living, please knock. If undead, please ring bell.”

Then I realized I could avoid the door interaction entirely.

I didn’t dress up scary. I didn’t decorate the house. My last minute purchases were, literally, candy and a tissue box. I’ve had the wig since 2011. The purple and black velvet medieval-ish dress has been in my closet since 2002 or so. I’ve had the LED tealight “candles” since before we moved to this house, so they’re at least four years old. I took the tissues out of the box and wrapped it in black construction paper and then in a layer of lace (a tank top that was destined for the giveaway pile anyway). I stapled the lace to the top of the box. In the box, I put candy and the votive candle, so that some vague flickery orange light would come out of it.

I turned off all the lights in the house. My garage faces the street, and a walkway leads around the side of the house to the front door, which is in a recessed entrance, not visible from the street or the walkway. I turned on the outdoor light, stood on the walkway with the pouch in my hands . . . and waited. Because I was already outside, nobody had to ring the bell. Anxiety trigger: avoided.

But I hadn’t prepared. Nothing about my house said that anyone was home. You had to be looking down between the houses as you passed, or you’d miss me completely. And that, it turned out, was the best part.

That alone startled a few people, minding their business and then suddenly realizing someone was there. And when that someone didn’t move . . .

Groups of kids gathered at the foot of my driveway, debating whether I was real. From the street, with me mostly back-lit, and the glowing thing in my hands, they couldn’t tell. I didn’t move until they could see me clearly. I let them wonder and debate, and felt like an NPC in a Pathfinder game, listening while the players decided their next move. Would they take the risk and approach me, or would they decide I was too dangerous?

I honestly had no idea that I’d end up being so scary. I was going for “creepy statue,” not “scare the crap out of people,” but it just goes to show that sometimes less is more. The less description you give people, the more mystery, the more their imaginations fill in the blanks. And on misty Halloween nights in particular, imaginations go to some very dark places.

I scared an older group away. One of the boys said, “nuh uh, I’ve seen how this movie ends,” and dragged his group to keep moving.

At one point, from a group of about ten kids debating my scaryness from the street, a young high-pitched voice yelled, “Stop calling me a wussy!” It was really hard not to laugh. I was extra nice to the little ones in that group.

Another boy, about 13 years old, I’d guess, said: “Nope. That’s a trap.”

“It’s a person,” his mom said.

“Nope, it’s a trap. It isn’t real.” So I slowly lifted my arms, extending the bag forward. He screamed. Close to tears, voice trembling, he said, “Say something! I’m not coming any closer until you prove if you’re a person and say something!”

I wasn’t out there to traumatize anyone, so I chose to break character. I bent double with laughter and said, “You guys are cracking me up. That was awesome.” Tension broken, the two kids and the mom approached. I gave them extra praise because they’d been extra brave.

Two very little ones were terrified, digging in their heels as their parents tried to push them forward.

An older boy in a gruesome bloody wolf mask, the tallest in a group of about fifteen brave kids, said “Trick or treat!” and added under his breath, “Please not a trick. Please not a trick.”

But as a rule, after I said “Happy Halloween” and gave them candy — that is, after I spoke and moved — most of them relaxed, laughed, and were excited to tell me all about how scared they’d been. And the parents all complimented me as well, saying mine was the best house in the neighborhood. That surprised me, since other houses decorated more or did fancier things. It also made me extremely proud.

And, as always, it ties back to writing. There’s a tendency among novice writers to over-explain the gore and horror, especially in relation to the rest of the narrative, to make sure the reader gets the image loud and clear. This is an insecure way to write, because it means you don’t trust the reader to “get it.” The solution isn’t to spell it out more plainly, it’s to manipulate the reader’s mind more. Letting the experiencer bring their own fears, anxieties, and perceptions to a situation makes it more powerful for them than drawing a complete picture, because if the picture is too complete there aren’t blanks for them to fill in. It’s not a conscious thing; it’s a result of us all being products of our experiences. But when you know that, you can play with it and twist it to your advantage.

I broke the Halloween script. I took away the preparation. I took away the doorbell. I took away what they expected from a trick-or-treat interaction. Some of them enjoyed it. Some of them took longer to adapt to it. Some of them were paralyzed by it. All of them were invested. All of them felt the endorphin rush of relief once they realized they were safe.

All of them will remember it.